Interior in Strandgade, Sunlight on the Floor by Vilhelm Hammershøi (c. 1901)

In November 1904, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke composed a letter to an acquaintance. He was requesting permission to stay with them in Copenhagen for nine to ten days the following month. Hoping to meet with a painter living in the city whose work had been occupying his mind since the summer. Contact with “this master” and “his great and eminent work”, he felt, would bring “enormous enrichment in my deepest and truest poetical strivings”. He explained his ultimate intention to produce an essay on him. But in a follow-up letter a year later he was left apologising for not yet being able to come up with anything at all from his trip. Tripped up by the challenge of creating a piece of writing that was “entirely and convincingly filled with the essence of this great master” and bemused by the difficulty of conversation with such a taciturn man. Rilke shook it off, though. Vilhelm Hammershøi’s paintings were “long and slow” and so naturally any engagement with them must not be rushed. He would find his way back to writing about his work eventually, he said, though he never did.

A Woman in an Interior, Strandgade 30 by Vilhelm Hammershøi (c. 1901)

One hundred and twenty one years later my wife and I visited Copenhagen on holiday. Keen not to overload our trip with another exhausting itinerary, ruining any sense of leisure by treating TripAdvisor as a checklist rather than suggestions, I identified seeing Hammershøi’s work in person as my greatest priority. I had encountered photos of his work online over the years, mostly of the eerily still interiors of his Copenhagen flat for which he is most famous. Taken in by their muted colours, spare compositions and the enigmatic figures facing away from view. Often in art galleries my wife and I will try and guess each other's favourite works in each part of the collection. She is very good at this, hopefully more due to the profound depth of her understanding of me than the banal predictability of my artistic taste, but with Hammershøi it is not exactly difficult. A Danish critic in 1885, Carl Hartmann, would bemoan how his work was shrouded in fog. Yes. Exactly. Isn’t that what we want?

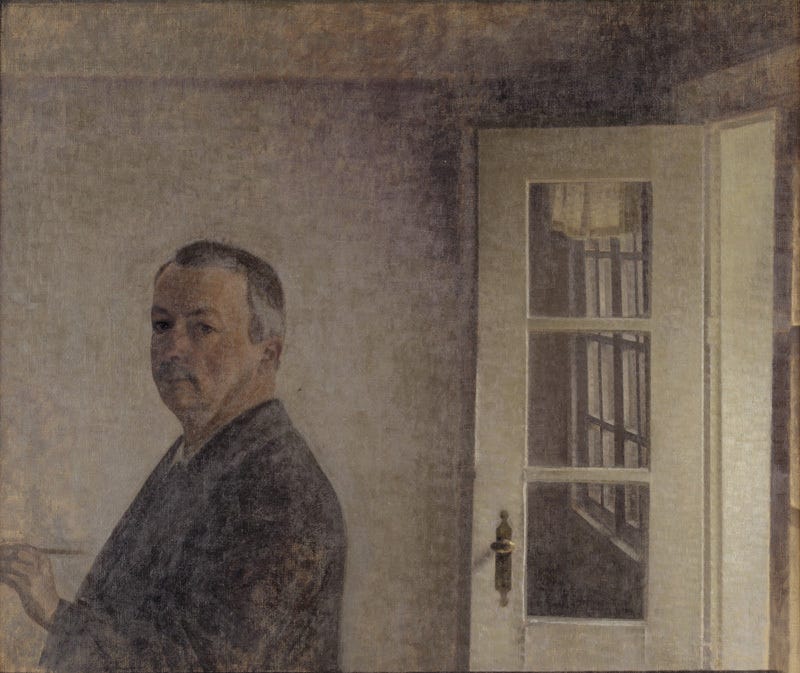

Self-Portrait, The Cottage Spurveskjul at Sorgenfri, North of Copenhagen by Vilhelm Hammershøi (c. 1911)

Hammershøi himself is similarly shrouded. He gave two interviews in his career, rarely appeared in public, and the correspondence that he didn’t manage to burn before his death mainly details his travel logistics. In one of these interviews when he is asked about his preoccupation with interiors, he replies “It is difficult to say”. The journalist then asks him about his reasons for using such a muted colour palette, he replies that “it’s quite impossible for me to say anything on the subject”. Michael Palin’s charming 2005 documentary on him concludes with a monologue arguing how his absence ultimately helps us to re-centre the importance of the artist's work over their life. Taking us back to what really matters. Though it’s hard not to feel like you would have to conclude that in the circumstances just to have something to wrap the program up with. We know that one of his teachers at the academy was referring to him when he talked about not wanting to dilute the style of “a student who painted in the oddest way”. We know he admired Whistler and unsuccessfully sought him out on a visit to London. The American's portrait of his mother, “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” seems like a proto Hammershøi in so many ways. Yet young Vilhelm had defined his own style long before he ever saw it. In fact if you flick through a chronological monograph of his work you find pretty much all the elements that would recur in his work are present within the first five years or so of his career.

Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 by James McNeill Whistler (c. 1871)

The catalogue of a retrospective of him held in Copenhagen and Munich in 2012 makes much of his travels and his links to the wider art world at the turn of the 20th century. There’s a nice art history twist in the notion that this private and reclusive figure whose pictorial world rarely escaped the confines of his own apartment, in fact was deeply connected to developments in the rest of the art world when everything was being upended. Perhaps his life functioning as a neat parallel with perceptions of Scandinavia at this time - a place far more modern and continental than one might assume. The radical slyly masquerading as conservative. Yet the curators' attempts to substantiate this only reveal the vast gaps in our understanding of him. Never have the phrases “ought to have”, “may well” and “hard to believe that”, all deployed regularly for his theoretical encounters, worked so hard as in this book. His presence in different cities at different times used to try and grasp at possible influences, while his responses to modern trends are often simply assumed in the absence of real evidence. This is hardly new. In the 1980s Dr Ibn Ostenfeld wrote an article trying to prove that Hammershøi was colour blind and this explained his particular use of perspective. Even in his own time one critic diagnosed him as a neurasthenic, seeing his work as evidence of him as a daring visionary of the new science of chronic exhaustion.

Palin’s approach then seems more useful, at least in avoiding the excesses of the over-extrapolating tendency. Yet it’s really hard not to glom onto things anyway. My favourite detail that I encountered in my reading about him since our holiday was a 1907 article in a London magazine called The Amateur Photographer”. It said that, while it rarely covered traditional art, it strongly encouraged its readers to study the works in Hammershøi’s latest exhibition as “examples of the extreme value of quiet spaces free from detail to give emphasis to the rest”. There is certainly something photographic about his compositions, you can really see that in contrast to artists working in the same genre. Set your phone to grayscale and search his work. At first glance the use of light is quite reminiscent of black and white photos. We know from his canvases that he shifted them around while painting to adjust the crop, perhaps like a photographer moving around his subject. Images of his apartment reveal how much he constantly adjusted domestic items like tables, bowls and lamps in and out of frame to create the most balanced composition.

Interior with a Woman Playing a Virginal by Emmanuel De Witte (c.1660-7)

It is intriguing too to learn that Hammershøi collected this newly emerging art form himself, his apartment stuffed with albums containing photos of Copenhagen and other art works that he liked. As too is the acknowledged influence on the pioneering Danish filmmaker Carl Theodore Dreyer, whose first silent film The President was full of visual nods to Hammershoi’s work. Yet there’s not much to this. There’s no sense that he is an actual photographer. I’m clearly reproducing the same impulse to reconstruct him from the few remaining pieces and searching for the same counterintuitive signs of modernity in him which annoyed me in my reading of others' work on him.

Shot from Carl Dreyer’s The President, 1920

At least, if you are reading this, then you can see I have gone 1-0 up against Rilke by successfully completing an essay on Hammershøi. Yet, in truth, the same thing which bedevilled him, his inability to get close to his works essence, has struck me too. I feel far more comfortable exploring personal aspects which I know are futile, and more at ease re-producing what other people have said about him than engaging directly. They normally get a bit closer than I can manage. Felix Kramer, for example, who talks about how Hammershøi constantly confronts viewers with their own expectations only to disappoint them. Or Kasper Monrad who talks about driving himself crazy trying to work out why a painting's subject was looking so intently at a coin. Looking at my favourite painting by him. At the beautiful play of the light on the carpet which is its central subject, while the mysterious woman at her desk to the side creates a sense of uneas……oh nevermind. Scroll up to the photo of it which opens this blog. These words are inadequate to the effect it produces. Maybe i’ll come back to it eventually.